This web page is created within BALTICS project funded from the European Union’s Horizon2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No.692257.

Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet

The Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet (abbreviated 67P) would probably not have become known to the general public if it had not been chosen by the European Space Agency as the destination for the Rosetta mission.

This small comet, about 4 km in size, was discovered on September 11, 1969, by two Soviet astronomers, Klim Ivanovich Churyumov and Svetlana Ivanovna Gerasimenko. Scientists had planned to see in the photograph the comet discovered in 1926 by the Spanish astronomer Josep Comas i Solà. A comet-like object was spotted on the very side of the photograph. After a closer look at the photographs, it was clear that a new comet had been discovered.

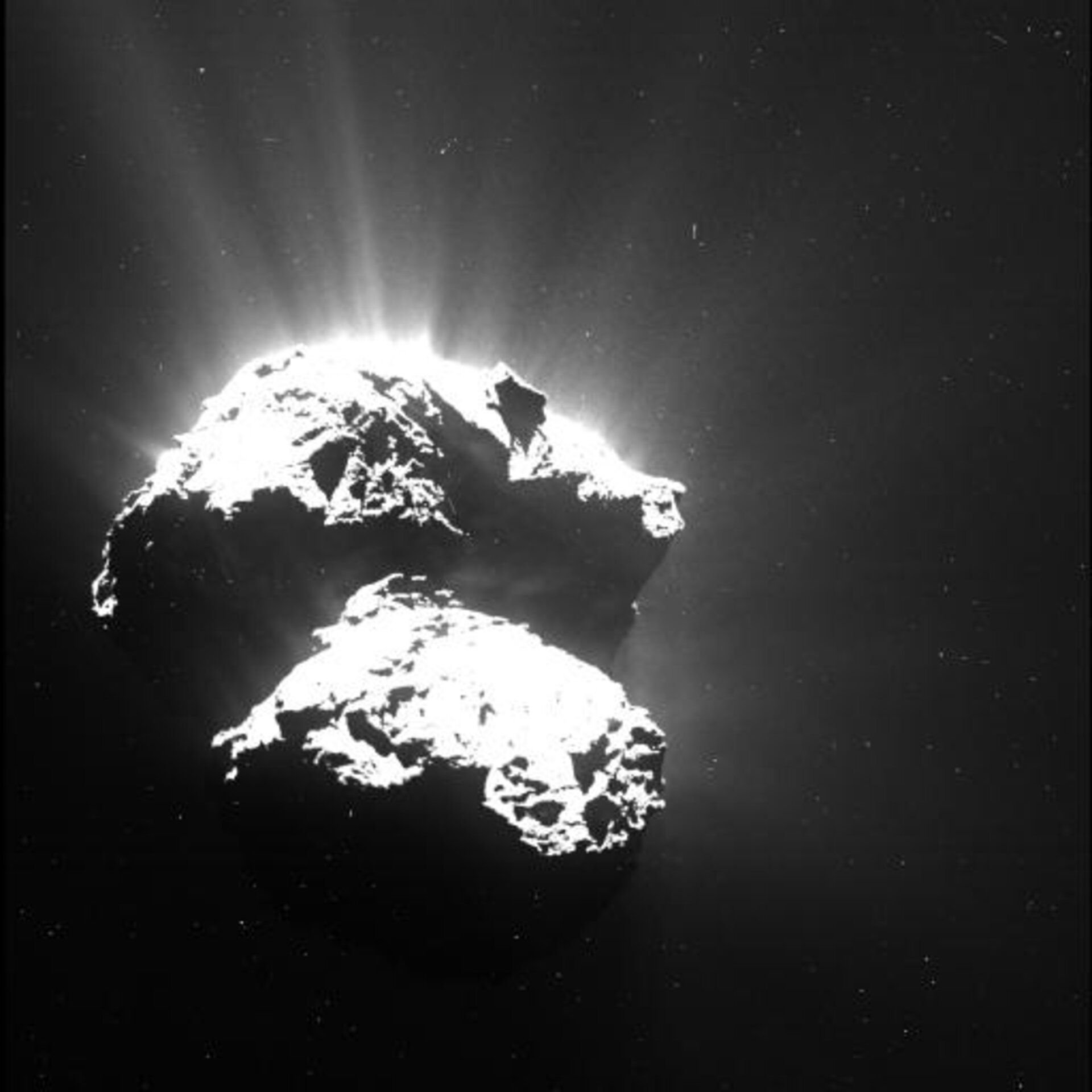

As the Rosetta spacecraft approached the comet, its unusual structure could be seen more and more clearly. The comet consists of two parts connected by a narrow passage. Rosetta’s destination was even compared to a rubber duck. It is believed that this unusual shape is formed by the slow collision of two objects.

Currently, the comet’s 67P orbital period is 6.45 years. It rotates around its axis every 12.4 hours. The perihelion of the comet is 1.2 astronomical units (slightly closer than the orbit of Mars) and the aphelion is 5.7 astronomical units (slightly further than the orbit of Jupiter) from the Sun.

Most likely, this comet was originally in the Kuiper belt. Its further fate has been influenced by the largest planet in the solar system, Jupiter, whose gravitational influence has left the comet in the inner regions of the solar system.

The last time the comet was in the perihelion or at the point of orbit closest to the Sun was on August 13, 2015. At that time, the comet was already accompanied by Rosetta, carefully gathering information about the changes in the comet’s activity as the Sun approached.

The comets are named after the ancient Egyptian deities. The largest part contains the names of the gods, but the smallest – various female deities.

The Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet is currently the only comet orbited by a man-made device, as well as the only comet-type object on which a landing device is stationed. Although the second part of the mission, in which Philae, which was not bigger than a washing machine, landed on the comet’s surface did not go according to plan, both Rosetta and Philae’s data have helped to better understand both the comet’s chemical composition and its behavior as it approaches and moves away from the Sun.

Comets are considered to be the objects through which water reached our planet at the beginning of Earth’s development. Rosetta data revealed that the isotopic composition of the water of the Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet (the ratio of heavy hydrogen or deuterium to hydrogen) does not correspond to that found in the Earth’s oceans. Most likely, objects like this comet are not the ones that brought water to Earth.

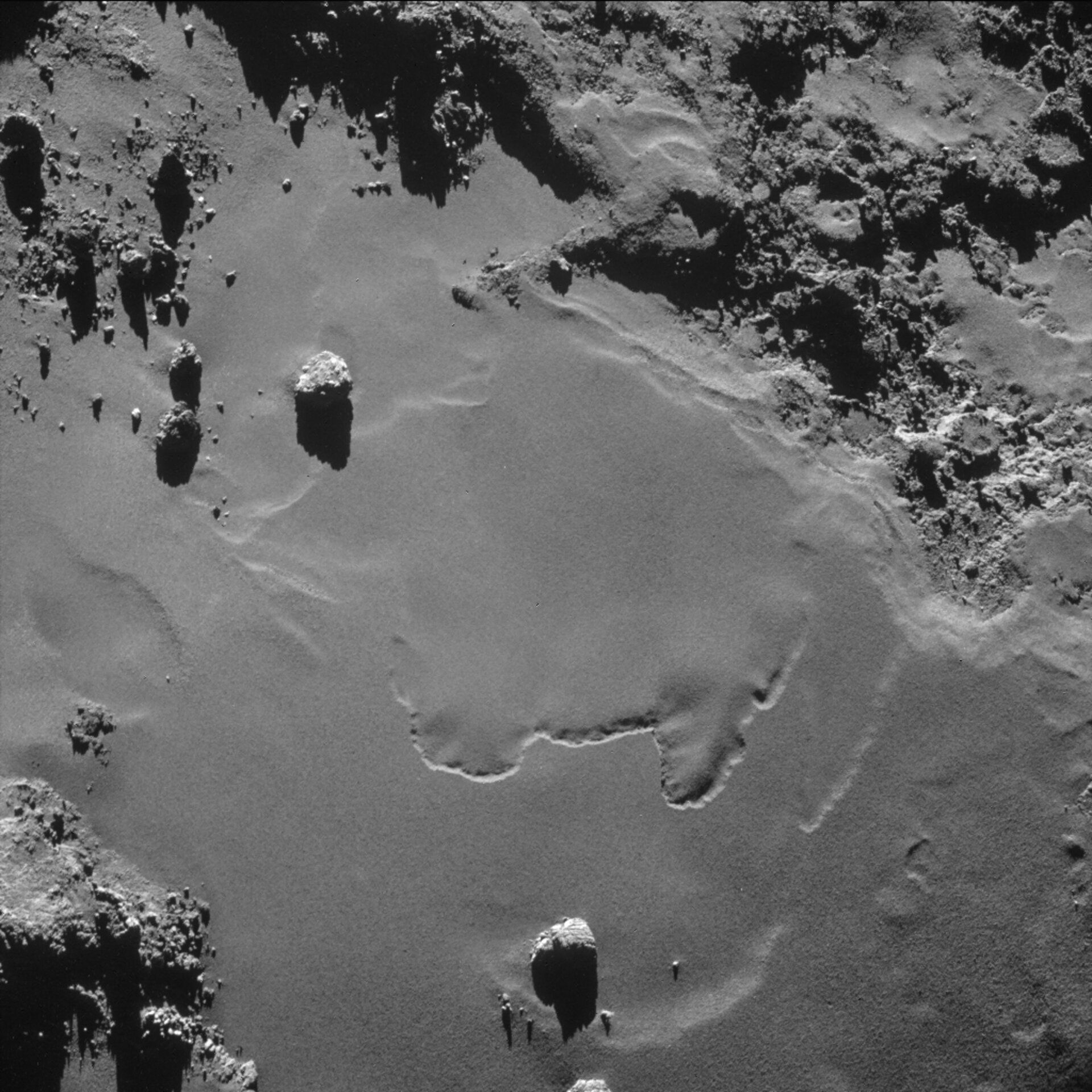

During its short operation, the Philae landing module was able to detect that the surface of the comet was covered with a layer of dust at least 20 cm thick, beneath which was a rock solid ice or a mixture of ice and dust.

Rosetta’s instruments helped to determine that organic molecules (such as methane, acetone, acetaldehyde, ethylene glycol, etc.) were found also on comet 67P, confirming the hypothesis that it was comets and asteroids that could bring to Earth the vital raw materials needed for life that could combine in the early environment of our planet and create the first origins of life.

Rosetta and Philae’s work is over, but interest in the Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet has not decreased. One of the future missions could be CAESAR, which would collect samples of the comet regolith and bring it back to Earth. The fate of this expedition will be decided in 2019, when NASA will choose either to send a device to a comet or to send another device to Saturn’s satellite Titan.