This web page is created within BALTICS project funded from the European Union’s Horizon2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No.692257.

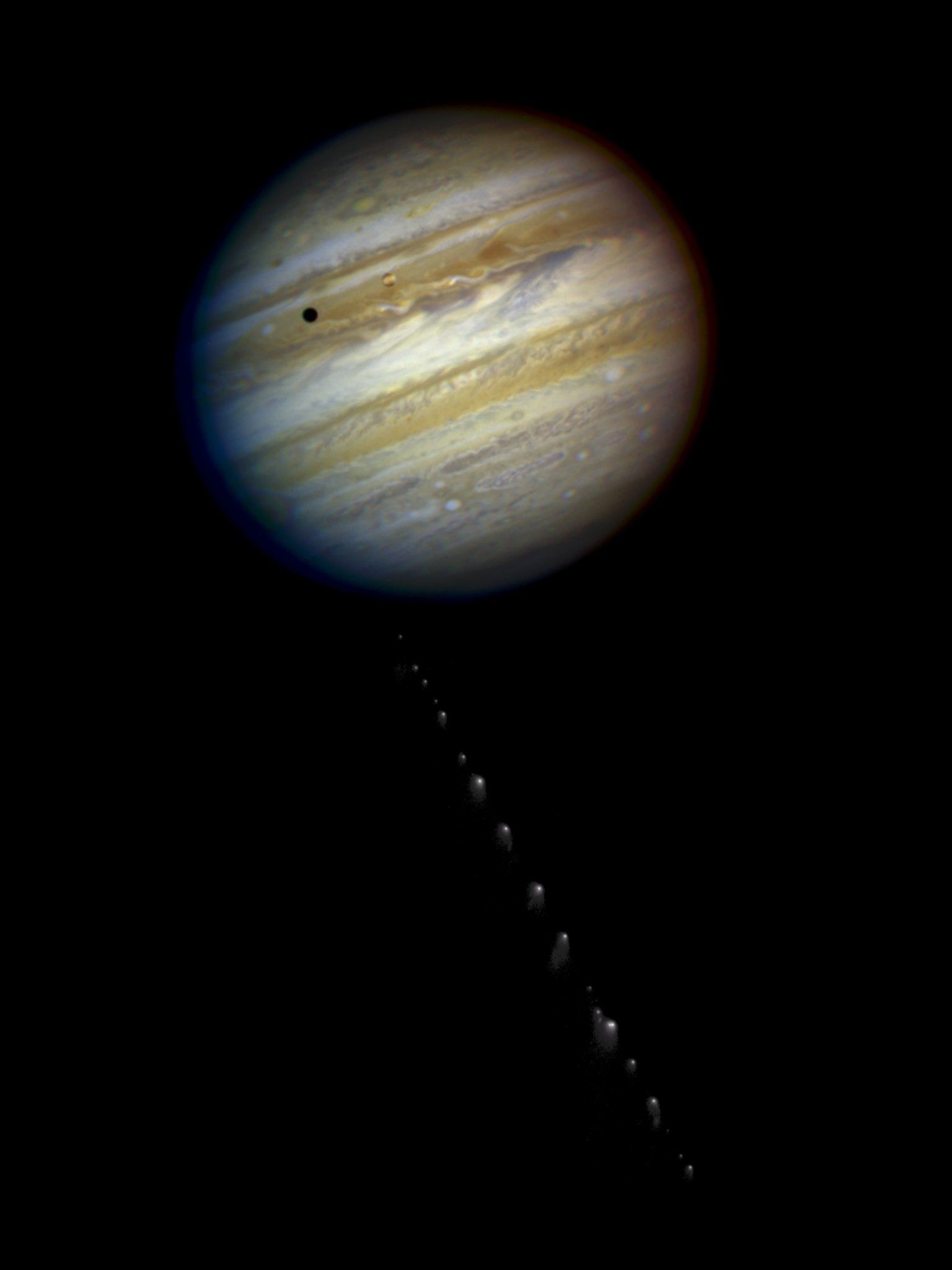

Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9

The Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 (D/1993 F2), discovered in a photograph taken on March 18, 1993, by one of the most successful comet hunters, Carolyn and Eugene Shoemaker and David Levy, no longer exists. It split into pieces in July 1992 and crashed into Jupiter two years later. The number “9” means that it was the ninth comet co-discovered by Shoemakers and Levy.

Exploration of the orbit revealed that this comet does not rotate around the Sun, but around Jupiter. It performed one orbit in about 2 years. It is likely that a giant planet had caught the glacial guest in its gravity in the early 1970s or late 1960s. Before that, it could have been a short period comet.

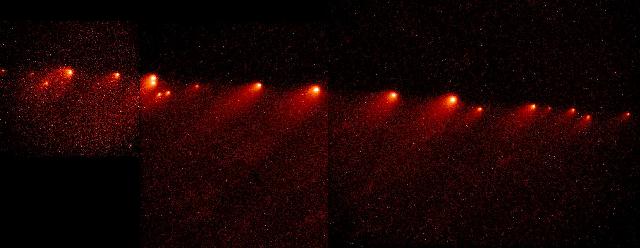

On July 7, 1992, the comet flew dangerously close to Jupiter. The planet's gravity shattered the comet's core. Subsequent orbit calculations indicated that in July 1994, fragments of the comet would strike Jupiter’s clouds. It was a great opportunity to study the collision of Jupiter, a comet and two objects in the Solar system.

The collision of the comet fragments was observed both on Earth and in space. The Galileo spacecraft, which was on its way to the Jupiter system, also took part in the observations. Galileo was the only one to see the moment of the collision, as fragments of the comet hit the opposite side of the Earth in the atmosphere of a giant planet, but relatively close to the “dawn” zone. As a result, the collision sites were visible from Earth within minutes.

Other spacecraft were also aimed at Jupiter, including the solar explorer Ulysses and Voyager 2, who is 44 astronomical units away.

The fragments of the comet were numbered alphabetically in flight order – the closest to Jupiter was the “A” fragment and the farthest was the “W”. A collision with the “A” fragment was observed on July 16, 1994, and the last, the “21” fragment, or “W”, struck Jupiter’s atmosphere on July 22. The most impressive collision was caused by the “G” fragment, leaving a dark “scar” of about 12,000 kilometers in the clouds of Jupiter.

The total power of the collision of all fragments with Jupiter was equivalent to 300 million atomic bombs. The atmosphere at the collision site was heated to 40,000 degrees Celsius. The

gas swirls in the collision rose about 3,000 kilometers above the clouds of Jupiter. The collisions of the 21 fragments were observed in the visible light for several months. Chemical changes in the atmosphere were recorded more than a year after the comet hit the giant planet. Deformities in Jupiter’s thinned rings, on the other hand, occurred more than 10 years after the collision.

As the technology of amateur astronomers improved and became more accessible to the general public, collisions with Jupiter were observed later, although they were much smaller than the Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9.

The grand event and the results of many observations support the idea that Jupiter serves as a barrier that protects the Earth and other inner planets by intercepting comets and asteroids. The largest planet in the Solar system is often referred to as a vacuum cleaner.

It is estimated that the core of the Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 may have been approximately 2 kilometers big. If it collided with the Earth, the consequences would be catastrophic. This event served as an incentive for space agencies in many countries to seriously begin searching for and

exploring objects that are near and potentially dangerous to Earth.